Lecture 03: Sampling and Simulation

2026-01-06

Recap

In the last lecture, we introduced some basic concepts of probability and random variables. We learned about:

- Probability

- Conditional probability

- Independence

- Probability functions

- Random variables

- Expectation (or expected value)

- Variance

- Probability distributions

Now that we have a good understanding of the basics of probability, we can start to explore how we deal with randomness computationally.

Sampling from probability distributions

A sample is a subset of data drawn from a more general population. That population can be thought of as a probability distribution – this distribution essentially describes how likely you are to observe different values when you sample from it.

We will quickly review some important concepts related to sampling.

IID sampling

Independent and identically distributed (IID) sampling

When we sample from a probability distribution, we often assume that the samples are independent and identically distributed (IID). This means that each sample is drawn from the same distribution and that the samples do not influence each other.

Coin flips are a good example of IID sampling. If you flip a fair coin multiple times, each flip has the same probability of being heads or tails (this is the “identically distributed” part), and the outcome of one flip does not affect the outcome of another (this is the “independent” part). The same is true for rolling a die!

IID in practice

We often apply this concept to more complex random processes as well, where we do not have such a clear understanding of the underlying process. For example, if we are sampling the heights of people in a city, we might assume that each person’s height is drawn from the same distribution (the distribution of heights in that city) and that one person’s height does not affect another’s.

Whether or not the IID assumption holds in practice is an important question to consider when analyzing data – for example, do you think that the heights of people in a family are independent of each other?

Sampling with and without replacement

Another important concept in sampling is the distinction between sampling with replacement and sampling without replacement.

Sampling with replacement means that after we draw a sample from the population, we put it back before drawing the next sample. This means that the same object / instance can be selected multiple times.

Sampling without replacement means that once we draw a sample, we do not put it back before drawing the next sample. This means that each individual can only be selected once. This can introduce dependencies between samples, as the population changes after each draw.

Quiz: Sampling

Simulating a random sample

We can simulate a random process by sampling from a corresponding probability distribution.

Note

Programmatic random sampling is not truly random, but rather “pseudo-random.” This means that the numbers generated are determined by an initial value called a “seed”. If you use the same seed, you will get the same sequence of random numbers. This is useful for reproducibility in experiments and simulations.

If you don’t specify a seed, the random number generator (RNG) will use a default seed that is typically based on the current date and time, which means that you will get different results each time you run the code.

Random sampling in Python

There are built-in functions in many programming languages, including Python, that allow us to sample from common probability distributions. For example, in Python’s NumPy library, we can use numpy.random module to sample from various distributions like uniform, normal, binomial, etc.

Normal distribution

The normal distribution is one of the most commonly used probability distributions in statistics. It is useful for modeling lots of real-world data, especially when the data tends to cluster around a mean (or average) value. The normal distribution is defined by two parameters: the mean (average) and the standard deviation (which measures how spread out the data is around the mean).

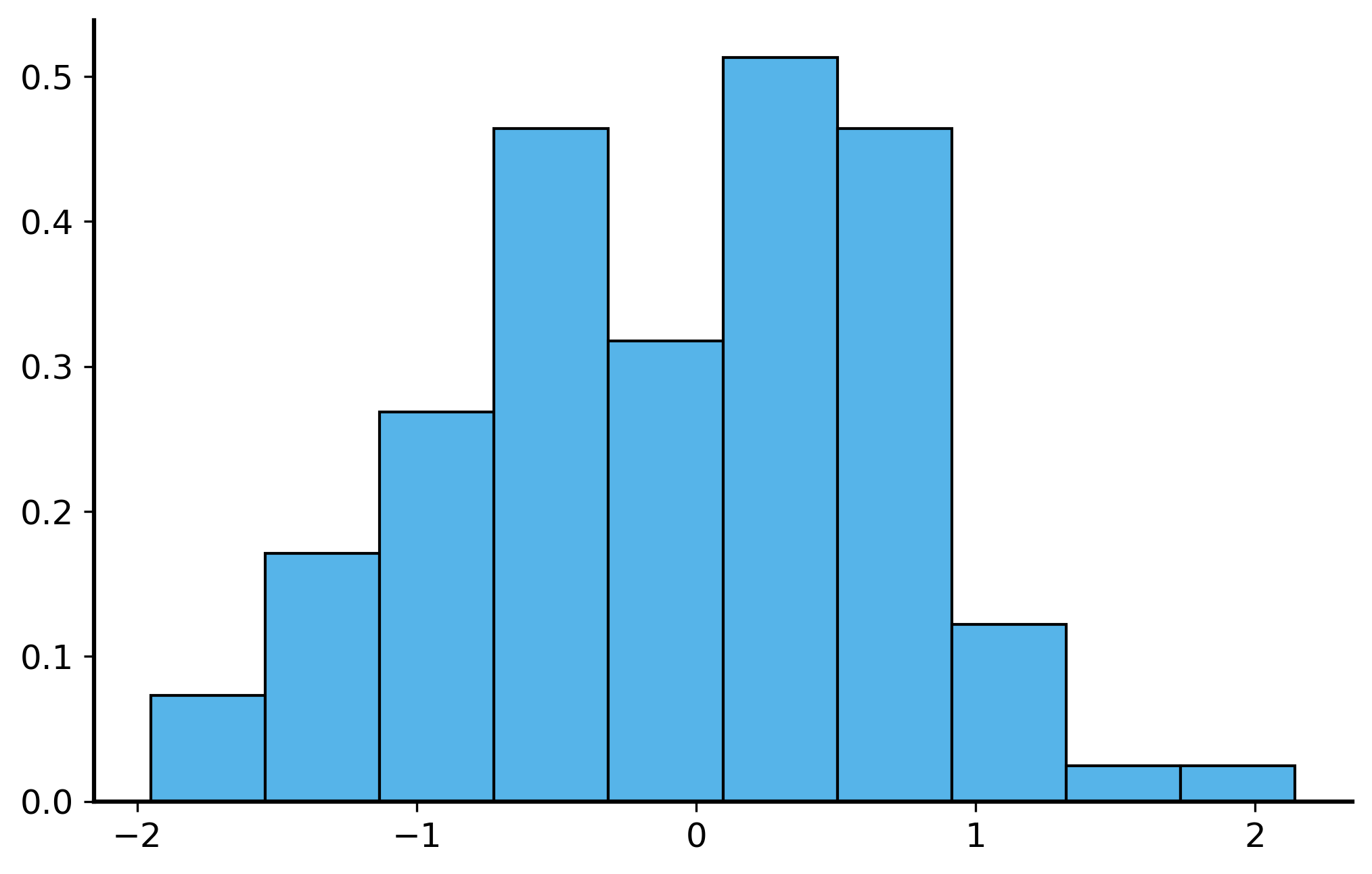

Sampling from a normal distribution

For example, to sample 100 values from a normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation 1, you can use:

Code

Samples:

[ 0.30471708 -1.03998411 0.7504512 0.94056472 -1.95103519 -1.30217951

0.1278404 -0.31624259 -0.01680116 -0.85304393 0.87939797 0.77779194

0.0660307 1.12724121 0.46750934 -0.85929246 0.36875078 -0.9588826

0.8784503 -0.04992591 -0.18486236 -0.68092954 1.22254134 -0.15452948

-0.42832782 -0.35213355 0.53230919 0.36544406 0.41273261 0.430821

2.1416476 -0.40641502 -0.51224273 -0.81377273 0.61597942 1.12897229

-0.11394746 -0.84015648 -0.82448122 0.65059279 0.74325417 0.54315427

-0.66550971 0.23216132 0.11668581 0.2186886 0.87142878 0.22359555

0.67891356 0.06757907 0.2891194 0.63128823 -1.45715582 -0.31967122

-0.47037265 -0.63887785 -0.27514225 1.49494131 -0.86583112 0.96827835

-1.68286977 -0.33488503 0.16275307 0.58622233 0.71122658 0.79334724

-0.34872507 -0.46235179 0.85797588 -0.19130432 -1.27568632 -1.13328721

-0.91945229 0.49716074 0.14242574 0.69048535 -0.42725265 0.15853969

0.62559039 -0.30934654 0.45677524 -0.66192594 -0.36305385 -0.38173789

-1.19583965 0.48697248 -0.46940234 0.01249412 0.48074666 0.44653118

0.66538511 -0.09848548 -0.42329831 -0.07971821 -1.68733443 -1.44711247

-1.32269961 -0.99724683 0.39977423 -0.90547906]

Sampling from a dataset

If you have a dataset and you want to sample from it, you can use the numpy.random.choice function to randomly select elements from the dataset (with or without replacement). If your dataset is in a pandas DataFrame, you can also use the sample method to randomly select rows from the DataFrame.

Code

# Sampling without replacement

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed=42)

subsample = rng.choice(samples, size=10, replace=False)

print("Sample:\n", subsample)

# another way to sample; note RNG can be different in different packages

pd.DataFrame(samples, columns=["Sample"]).sample(n=10, replace=False, random_state=42)Sample:

[-1.32269961 -1.13328721 -0.01680116 -1.68286977 0.54315427 -1.68733443

0.85797588 -0.85304393 -0.04992591 -0.36305385]| Sample | |

|---|---|

| 83 | -0.381738 |

| 53 | -0.319671 |

| 70 | -1.275686 |

| 45 | 0.218689 |

| 44 | 0.116686 |

| 39 | 0.650593 |

| 22 | 1.222541 |

| 80 | 0.456775 |

| 10 | 0.879398 |

| 0 | 0.304717 |

Custom distributions

If you want to sample from a custom distribution, you can also use the numpy.random.choice function to sample from a list of values with specified probabilities.

Here’s an example of how to sample 100 dice rolls with a rigged die that has a 50% chance of rolling a 6, and a 10% chance of rolling each of the other numbers (1-5):

Code

array([4, 6, 6, 6, 5, 3, 6, 1, 6, 6, 6, 4, 6, 6, 6, 2, 5, 1, 2, 6, 6, 6,

4, 4, 5, 2, 2, 5, 3, 6, 5, 6, 6, 4, 6, 6, 4, 3, 6, 2, 2, 1, 6, 6,

6, 6, 5, 6, 2, 2, 6, 5, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 4, 1, 5, 3, 5, 6, 3, 1, 3,

3, 6, 6, 6, 6, 5, 6, 2, 1, 1, 6, 5, 2, 6, 2, 6, 5, 4, 4, 6, 4, 1,

2, 6, 6, 6, 3, 6, 6, 6, 5, 3, 1, 6])Simulating more complex processes

Sometimes real-world processes are complex, and the samples we take are not independent. The simplest version of non-independence is sampling without replacement.

Consider dealing poker hands from a standard deck of cards. When you deal a hand, you draw cards one at a time, and each card drawn affects the next card that can be drawn (because you do not put the card back into the deck).

Dealing cards example

Code

# Make a deck of cards (Ace is 1, King is 13)

deck = np.arange(1, 14).repeat(4) # 4 suits, each with cards 1 to 13

print("Deck of cards before shuffling:\n", deck)

deck = np.random.permutation(deck)

print("Deck of cards after shuffling:\n", deck)

# deal 2 cards to each of 4 players

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed=21)

# Get flat indices of 8 cards from deck

# we want to know exactly which cards are dealt

chosen_indices = rng.choice(len(deck), size=8, replace=False)

hands = deck[chosen_indices].reshape(4, 2)

print("Hands dealt to players:\n", hands)

# remove the dealt cards from the deck

remaining_deck = np.delete(deck, chosen_indices)

print("Remaining cards in the deck:\n", remaining_deck)

board = np.random.choice(remaining_deck, size=5, replace=False)

print("Community cards on the board:\n", board)Deck of cards before shuffling:

[ 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 6 6 6 6

7 7 7 7 8 8 8 8 9 9 9 9 10 10 10 10 11 11 11 11 12 12 12 12

13 13 13 13]

Deck of cards after shuffling:

[13 12 2 12 4 1 3 6 7 10 2 3 9 5 9 13 9 6 9 1 2 12 11 8

7 8 5 7 7 13 4 11 11 1 10 4 3 3 5 6 8 8 5 4 6 11 1 13

10 12 2 10]

Hands dealt to players:

[[12 4]

[ 4 5]

[ 6 13]

[11 9]]

Remaining cards in the deck:

[13 12 2 12 1 3 6 7 10 2 3 9 9 13 9 1 2 12 8 7 8 5 7 7

4 11 11 1 10 3 3 5 6 8 8 5 4 6 11 1 13 10 2 10]

Community cards on the board:

[12 11 13 11 12]Multi-step simulations

But it can get even more complex than that. In many real-world scenarios, the process of generating data involves multiple steps or conditions that affect the outcome.

In these cases simulation might not be as straightforward as sampling from a single distribution (which takes just one or two lines of code). We then tend to write loops that simulate the process step by step, keeping track of the state of things as we go along.

Busker example

Let’s consider an example of a musician busking for money in Rittenhouse Square. The musician’s earnings might depend on various factors like the weather and and the number of passersby. To keep it simple, let’s assume that the musician earns $3 for every passerby who stops to listen. Of course, not every passerby will stop – let’s pretend every passerby has the same 20% chance of stopping.

The musician might want to know how much money they can expect to earn in a day of busking. We can simulate this process by generating a random number of passersby and then calculating the earnings based on the stopping probability.

Poisson distribution

Poisson distribution

The Poisson distribution is commonly used to model the number of events that occur in a fixed interval of time or space, given a known average rate of occurrence. It assumes that the events occur independently and at a constant average rate. In our example, we can use the Poisson distribution to model the number of passersby in a given time period (e.g., one hour of busking).

Busker simulation code

Code

n_days = 5

# simulate whether it rains each day

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed=42)

rain_probabilities = rng.uniform(0., 0.7, size=n_days)

total_earnings = 0 # initialize a variable to keep track of total earnings

for day in range(n_days):

# For each day, decide if it rains based on the probability

did_it_rain = rng.binomial(n=1, p=rain_probabilities[day])

print(f"Day {day + 1} ({rain_probabilities[day]:.2%} chance): {'Rain' if did_it_rain else 'No rain'}")

# Based on the outcome, the number of passersby changes

if did_it_rain:

passersby = rng.poisson(lam=50) # fewer passersby when it rains

else:

passersby = rng.poisson(lam=200) # more passersby when it doesn't rain

print(f"\t Number of passersby: {passersby}")

# Simulate the number who stop to listen to the busker

listeners = rng.binomial(n=passersby, p=0.2) # 20% of passersby stop

print(f"\t Number of listeners: {listeners}")

# Compute the busker's daily earnings

earnings = 3 * listeners # $3 per listener

print(f"\t Daily earnings: ${earnings}")

print("-" * 40)

total_earnings += earnings

print(f"Total earnings over {n_days} days: ${total_earnings}")Day 1 (54.18% chance): No rain

Number of passersby: 211

Number of listeners: 41

Daily earnings: $123

----------------------------------------

Day 2 (30.72% chance): No rain

Number of passersby: 226

Number of listeners: 54

Daily earnings: $162

----------------------------------------

Day 3 (60.10% chance): Rain

Number of passersby: 51

Number of listeners: 13

Daily earnings: $39

----------------------------------------

Day 4 (48.82% chance): Rain

Number of passersby: 56

Number of listeners: 17

Daily earnings: $51

----------------------------------------

Day 5 (6.59% chance): No rain

Number of passersby: 212

Number of listeners: 34

Daily earnings: $102

----------------------------------------

Total earnings over 5 days: $477Exercise: Simulate Weekly Earnings

Task: Simulate the expected earnings of a busker over a week. Run the simulation 1000 times and calculate the average.

Solution

Solution

import numpy as np

def busk_one_week(rng, n_days=7):

"""Simulate weekly earnings of a busker."""

rain_probabilities = rng.uniform(0., 0.7, size=n_days)

total_earnings = 0

for day in range(n_days):

did_it_rain = rng.binomial(n=1, p=rain_probabilities[day])

if did_it_rain:

passersby = rng.poisson(lam=50)

else:

passersby = rng.poisson(lam=200)

listeners = rng.binomial(n=passersby, p=0.2)

total_earnings += 3 * listeners

return total_earnings

# Run 1000 simulations

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed=33)

earnings_by_week = [busk_one_week(rng) for _ in range(1000)]

average_earnings = np.mean(earnings_by_week)

print(f"Average weekly earnings: ${average_earnings:.2f}")