Lecture 04: Data Generating Processes and Statistical Models

2026-01-06

Recap: Sampling and Simulation

Last lecture we learned:

- How to sample from probability distributions

- IID sampling and sampling with/without replacement

- How to simulate complex random processes step by step

Today we formalize these ideas with data generating processes and statistical models.

Data Generating Processes

A key insight: all data is generated by some underlying process

- The process can be simple or complex

- Deterministic or stochastic

- Observed or unobserved

Thinking about data generating processes (DGPs) is fundamental to analyzing data.

Statistical Models

A statistical model is a formal mathematical representation of a DGP.

- Describes the probability distribution of the data

- Allows precise statements about generated data

- Tells us likelihood of certain values, expected values, etc.

Example: Coin Flips

DGP: Flipping a coin (heads or tails)

Statistical Model: Bernoulli distribution

\[P(X) = \begin{cases} p & \text{if } X = 1 ~\text{(heads)} \\ 1 - p & \text{if } X = 0 ~\text{(tails)} \end{cases}\]

For a fair coin: \(p = 0.5\)

Models are Reductive

The Bernoulli model ignores many factors:

- Weight of the coin

- Force of the flip

- Air resistance

But it accurately describes the outcomes — and that’s what matters!

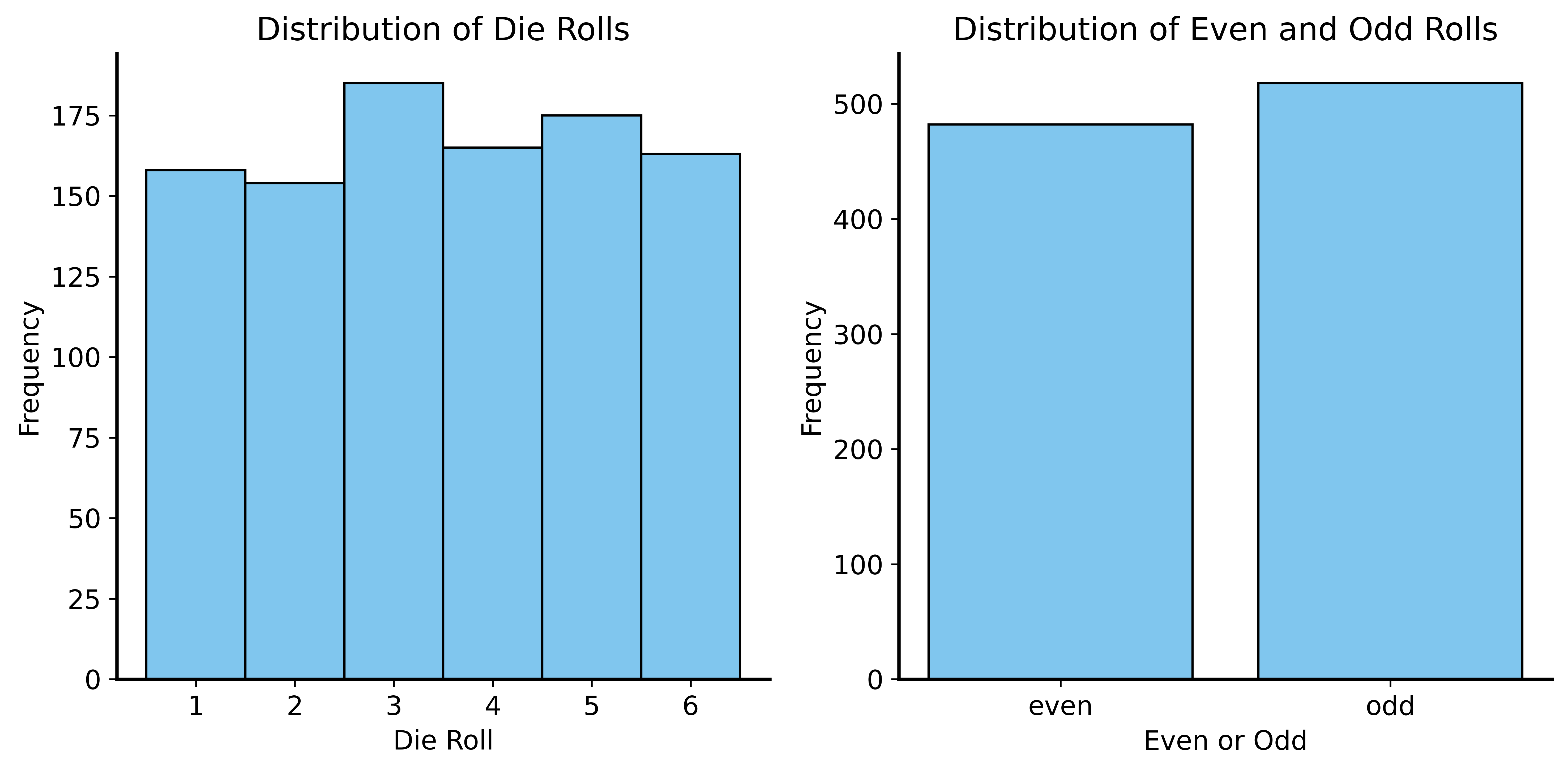

Example: Dice → Coin

Roll a die 100 times. Record whether each roll is even or odd.

- 3 even numbers (2, 4, 6)

- 3 odd numbers (1, 3, 5)

- Each outcome has probability 1/6

Result: P(even) = P(odd) = 0.5

This is statistically identical to flipping a fair coin!

Dice → Coin Visualization

The Goal of Statistical Modeling

Find a simple model that captures essential features of the DGP.

- We don’t always know the true DGP

- Often we don’t know anything about it!

- Approach: “guess and check”

- Start simple

- See how well it describes the data

- Try more complex models if needed

Challenges with Finite Samples

Hard to tell if you have a good model with limited data.

Extreme example: Flip a coin once

- Observed proportion of heads: 0 or 1

- Expected proportion: 0.5

- Impossible to observe the expected proportion!

You can’t learn much about tendencies from a single observation.

The Roommate Problem

Scenario: You and your roommate flip a coin to decide who takes out the trash.

- You always choose tails

- Best of 10 series

- Result: 3 heads, 7 tails

Your roommate: “That’s not fair! You rigged the coin!”

Is your roommate justified?

Distinguishing Models

| Scenario | P(3 heads in 10 flips) |

|---|---|

| Fair coin (p = 0.5) | ~11.7% |

| Biased coin (p = 0.25) | ~25.0% |

With 10 flips, you have some information but not enough to be confident.

Distinguishing Models (More Data)

| Scenario | P(30 heads in 100 flips) |

|---|---|

| Fair coin (p = 0.5) | ~0.002% |

| Biased coin (p = 0.25) | ~4.6% |

With more data, evidence becomes much stronger!

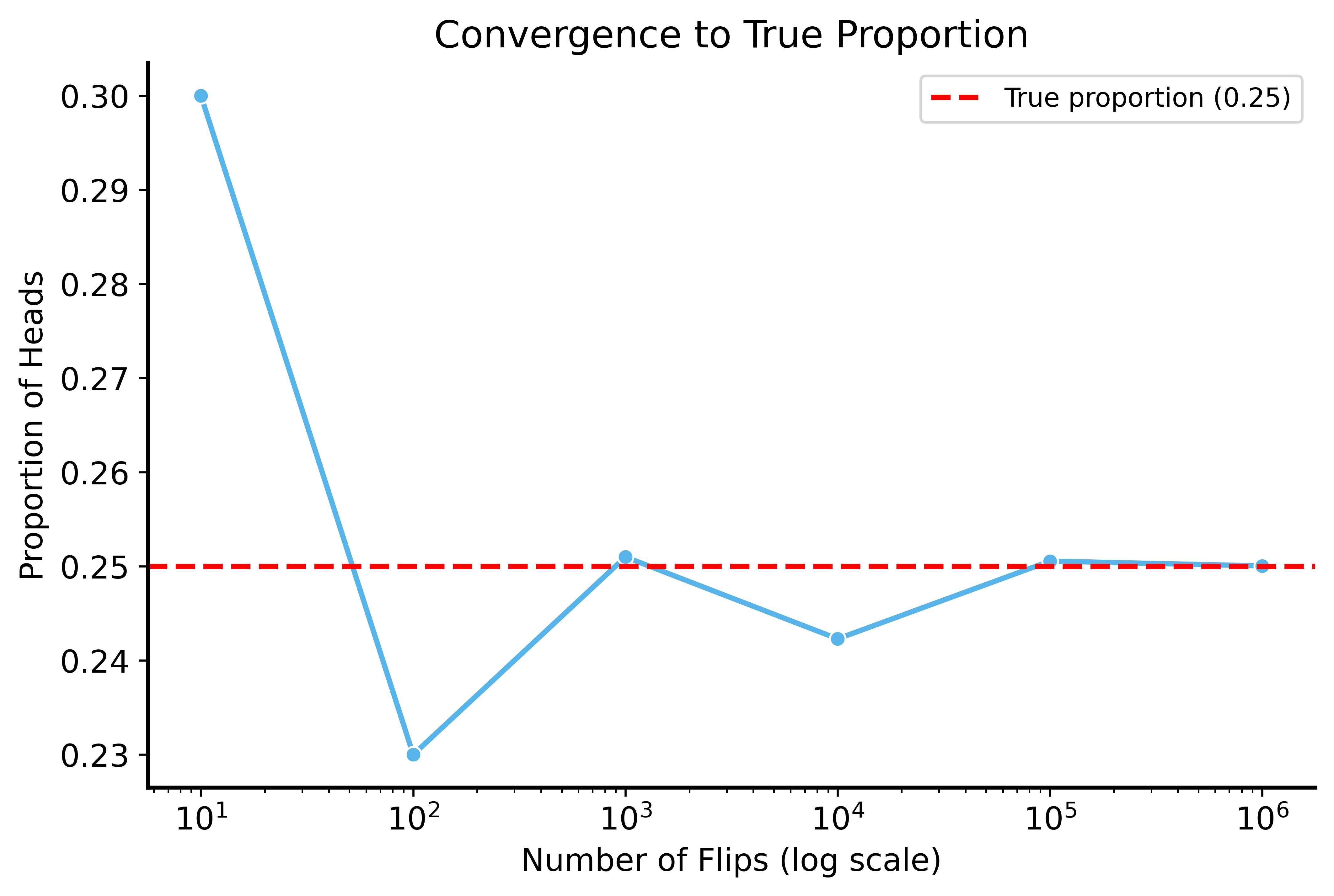

Law of Large Numbers

As sample size increases, the sample mean converges to the population mean.

Formally: Let \(X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n\) be i.i.d. random variables with expected value \(\mathbb{E}[X]\)

\[\mathbb{P} \left[\lim_{n \to \infty} \bar{X}_n = \mathbb{E}[X]\right] = 1\]

The sample mean \(\bar{X}_n = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i\) converges to the true mean.

LLN in Action

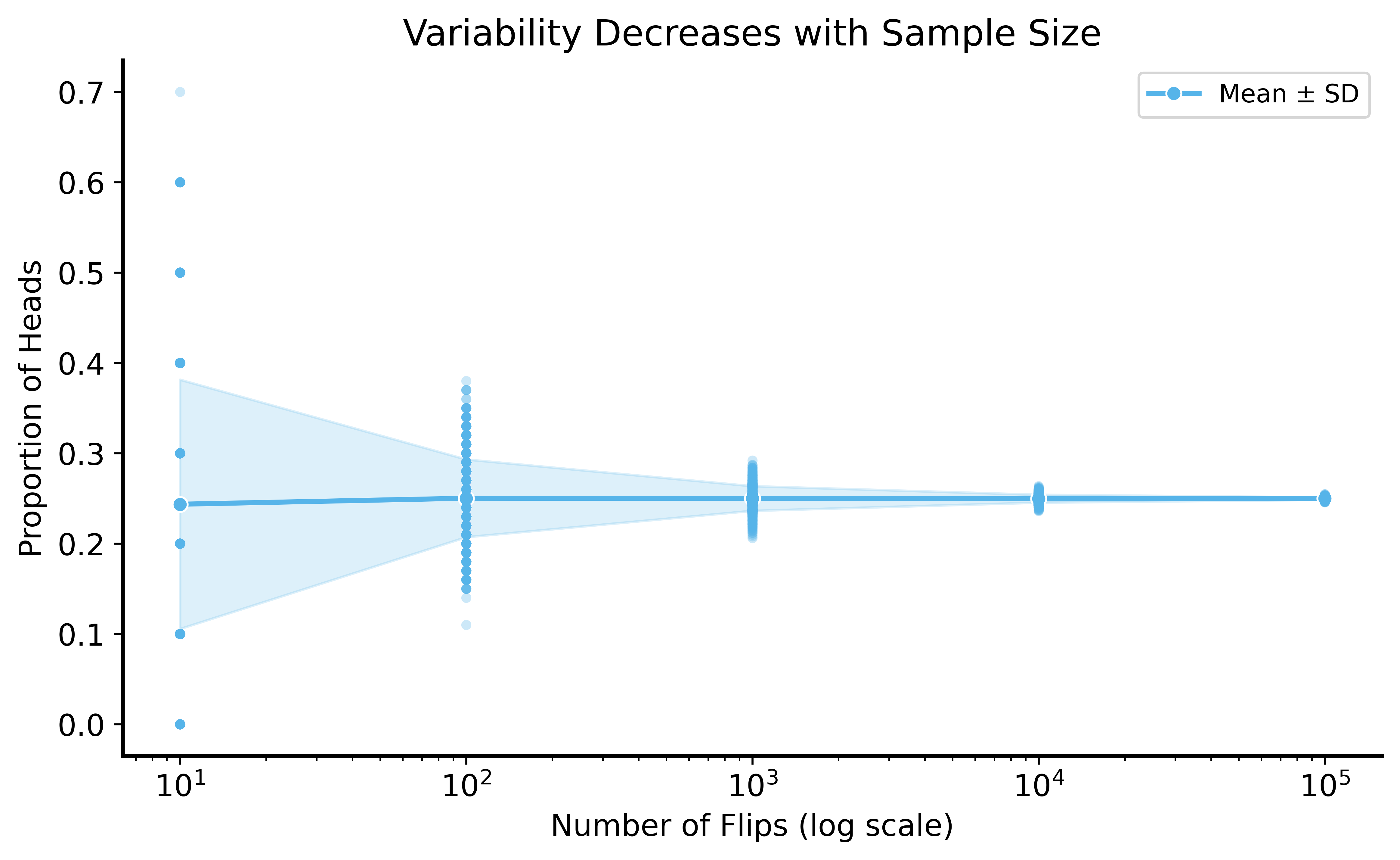

LLN: Multiple Simulations

Key Insight from LLN

As sample size increases:

- Sample mean gets closer to true mean (on average)

- Variability decreases — estimates become more consistent

Practical implication: More data → more confident conclusions

Unbiased Estimators

Notice: even with high variability in small samples, the sample mean is centered around the true mean.

An estimator is unbiased if its expected value equals the true parameter.

\[\mathbb{E}[\bar{X}] = \mu\]

The LLN tells us that as \(n \to \infty\), the variance of the estimator decreases.

Central Limit Theorem

The sample mean converges to a normal distribution, regardless of the original distribution!

Formally: Let \(X_1, \ldots, X_n\) be i.i.d. with mean \(\mu\) and variance \(\sigma^2\)

\[\bar{X}_n \xrightarrow{d} N\left(\mu, \frac{\sigma^2}{n}\right)\]

Even if \(X\) is not normal, the average of many \(X\)’s is approximately normal!

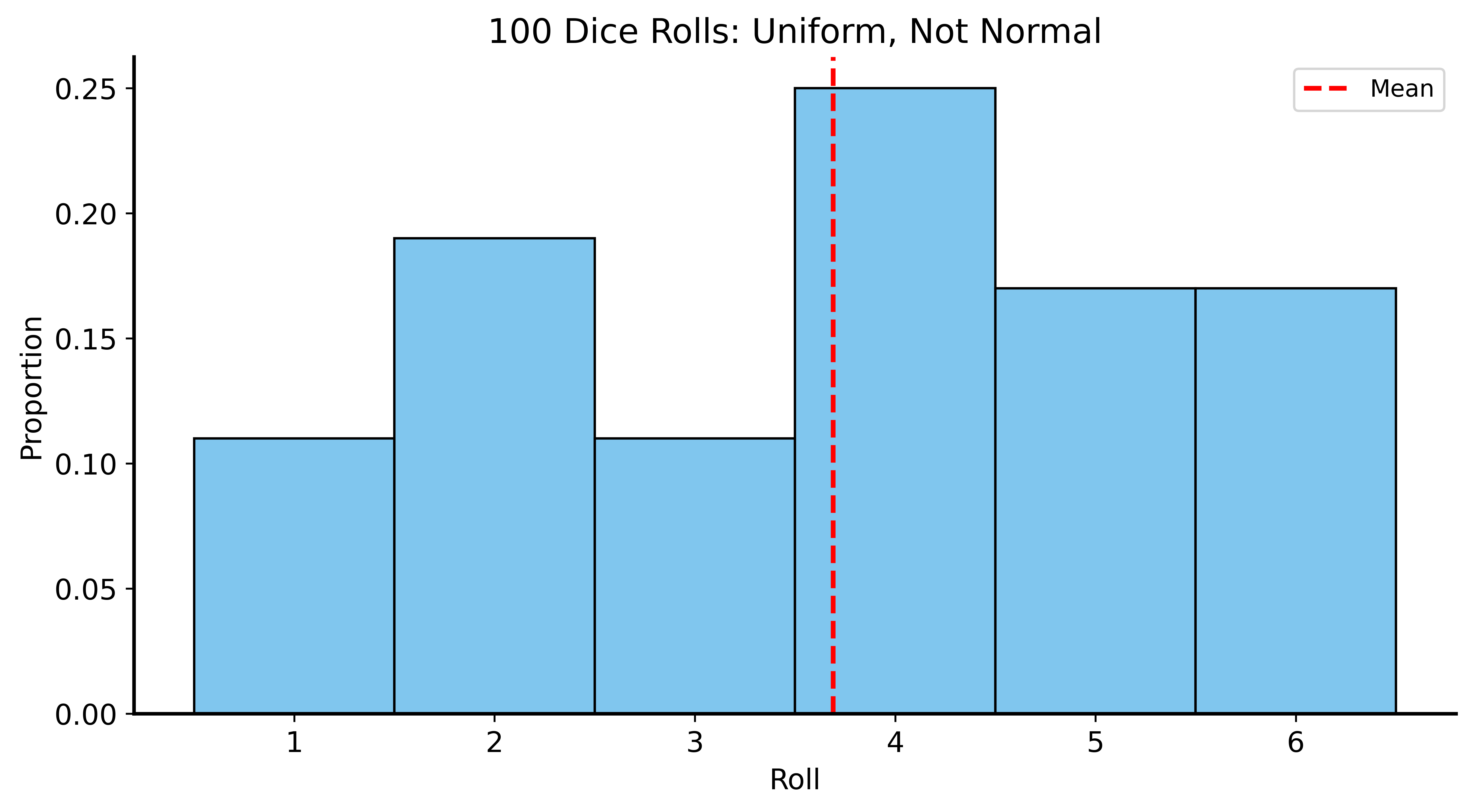

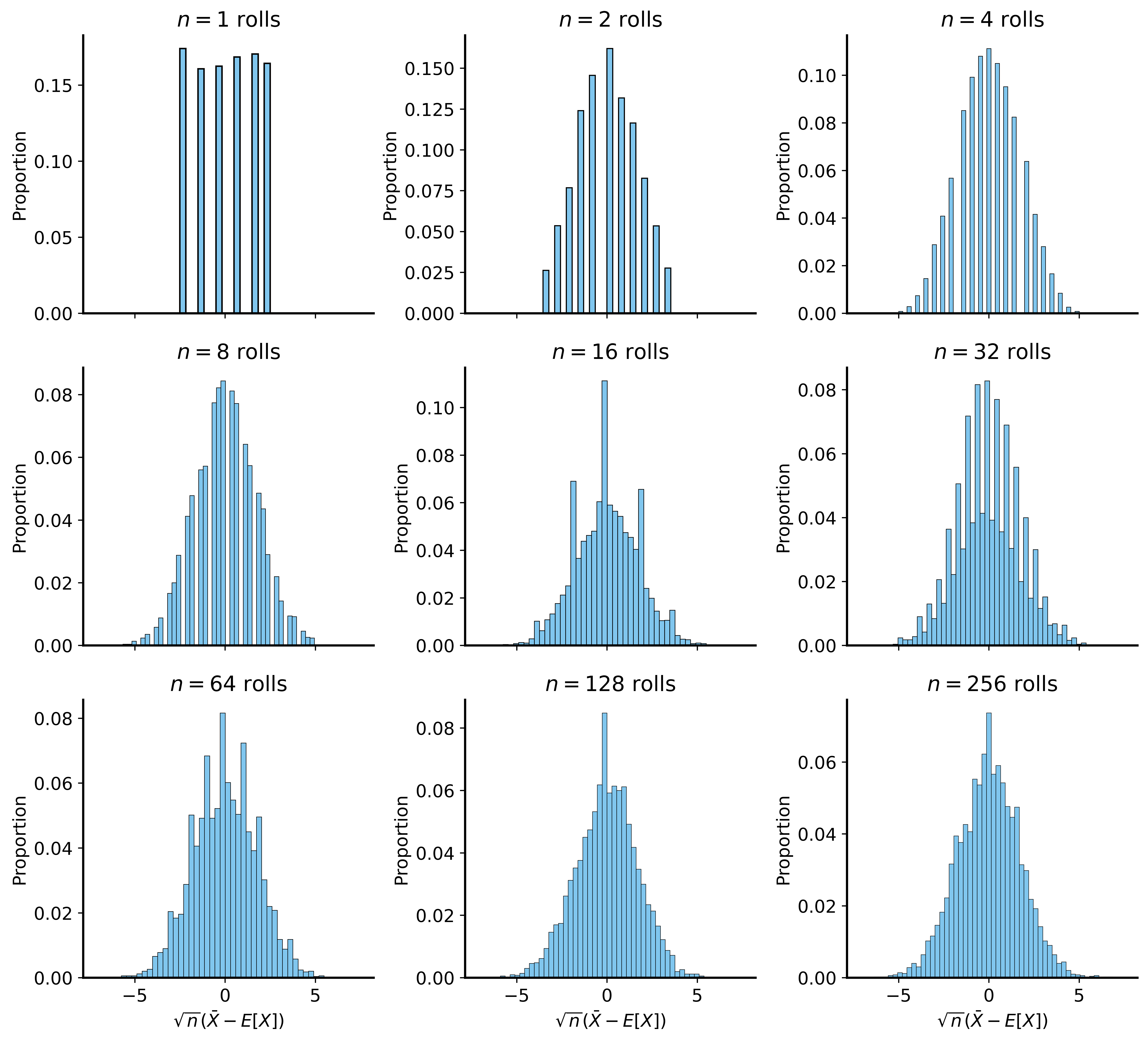

CLT Example: Dice Rolls

Rolling a die: uniform distribution from 1 to 6

- Expected value: \(E[X] = 3.5\)

- Clearly not normal

But what about the average of many dice rolls?

CLT Example: Single Die

CLT in Action

Why CLT Matters

Even when we don’t know the original distribution:

- We can use the normal distribution to model the sample mean

- This works for a huge class of DGPs

The normal distribution is:

- Symmetric

- Well-studied

- Easy to work with mathematically

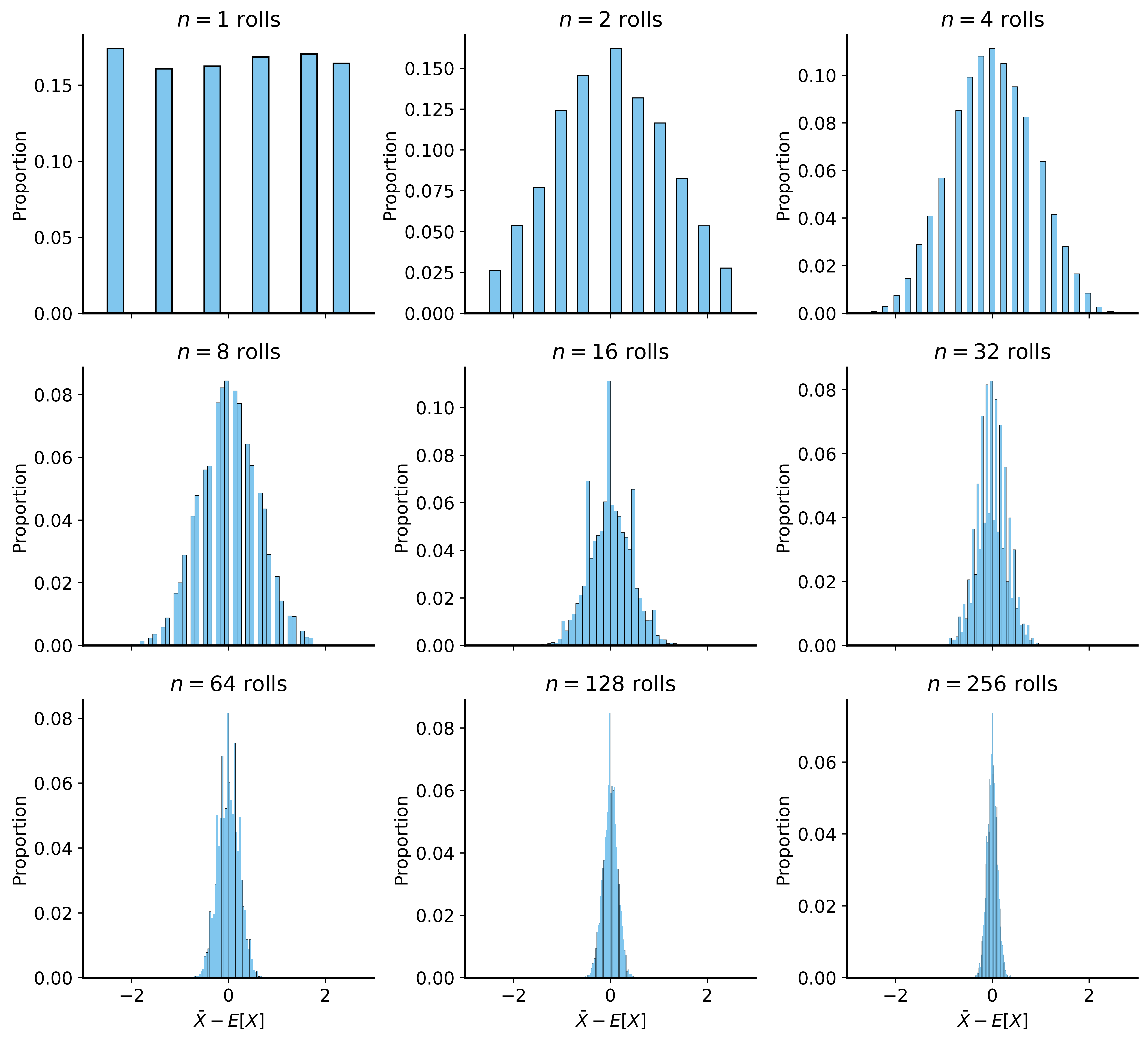

Standard Errors

The CLT tells us the sample mean has variance \(\frac{\sigma^2}{n}\)

Standard error = standard deviation of the sample mean:

\[SE = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\]

As \(n\) increases, SE decreases → estimates become more precise

Standard Errors Visualized

Summary

Data Generating Processes

- All data comes from some underlying process

- Statistical models are simplified representations of DGPs

Law of Large Numbers

- Sample means converge to true means as \(n \to \infty\)

- More data → more confident conclusions

Central Limit Theorem

- Sample means are approximately normal (for large \(n\))

- Standard error decreases as \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\)

Next Time

Hypothesis Testing

- How to formally test claims about data

- Using sampling distributions to quantify uncertainty

- Making decisions under uncertainty